When Gavin Newsom ran for governor of California in 2018, the long-running housing crisis in its major cities was already metastasizing. Statewide, the median home sale price in 2012 was $321,748; by 2018, it had risen to $571,058, a 75 percent increase in just six years. But Newsom had a plan: if elected, he would stimulate the construction of 3.5 million new homes — 3.5 million being the magic number that McKinsey said California would need in order to close its housing gap.

By 2020, the median home price at sale had risen to $646,245, and the worst consequences of the housing crisis were becoming even harder to ignore. Homelessness, and in particular visible street homelessness, was soaring to new heights. The previous year, in Los Angeles County alone, 1,267 people had died while homeless. Newsom declared that it was time for bold action: he would dedicate the entirety of his annual State of the State speech to the subject of homelessness. “I don’t think homelessness can be solved,” he would declare in the speech’s peroration. “I know homelessness can be solved. This is our cause. This is our calling.”

And since then? Well, in the years since Newsom’s inauguration, his own Department of Housing and Community Development estimates that California has built slightly fewer than half a million homes. The median home sale price in 2023 was $827,300. And homelessness is worse than it has ever been; between 2018 and 2024, according to the federal Department of Housing and Urban Development’s annual point-in-time count, homelessness statewide rose 44 percent.

While the overall picture is bleak, there have been some policy victories along the way, without which things would be even worse. California homeowners have built tens of thousands of accessory dwelling units (ADUs), thanks to an ongoing ADU law reform effort that the legislature initiated in 2016. When the federal government responded to the COVID-19 pandemic by unleashing a flood of emergency aid, California used some of the windfall to launch Homekey, a project that has since created more than 15,000 units of housing for homeless people. And the legislature recently reauthorized SB 35 (2017) — now dubbed SB 423 — a law that has produced more than 18,000 largely below-market-rate homes and promises to facilitate the construction of tens of thousands more over the coming years.

But these small victories, while good and necessary, are deeply insufficient. And it is striking how many of them were achieved more or less in the governor’s absence. Homekey was an administration effort, but the land use reforms coming out of the legislature were very much not. As far as I can tell, Newsom has not spent political capital in support of a single major housing bill, let alone personally twisted arms in the legislature to get it passed. The housing bills that have reached his desk arrive there unsullied by his fingerprints.

Instead of following through on his vow to spur large scale housing production, Newsom drifted off toward other priorities. First, of course, it was COVID-19. Then it was Care Courts, which seemed to represent a change of emphasis when it came to homelessness: instead of focusing on Housing First and home production, Newsom would direct the administration’s energies toward mental health treatment.

That lasted just long enough for the Care Courts bill to make it out of the legislature. Within a couple years, the governor’s attention had wandered to gas prices: he demanded a last-minute special legislative session to address the cost at the pump. This was followed by another special session to “Trump-proof” California. But as Trump’s inauguration neared, Newsom decided to switch up his tactics; instead of acting as a self-appointed general in the anti-Trump resistance, he decided that he should try to do DOGE one better. Now the priority du jour is using artificial intelligence to make government more efficient and dragging state workers back into the office.

Newsom’s predecessor, Jerry Brown, was an intensely focused governor: he picked a handful of priorities — cap and trade carbon pricing, school funding reform, high speed rail — and pursued them relentlessly, often to the detriment of other, equally pressing state-level needs. In contrast, Newsom has labeled virtually every issue a high priority, and lavished special consideration on basically none of them. His tenure as governor has been defined by an endless cascade of bold promises, soaring exhortations, impulsive feints in one direction or another, and no follow-through.

Now Newsom’s tenure is almost at an end. He is getting termed out in January 2027, and a crowded field of would-be successors (including, rumor has it, Kamala Harris) are mentally redecorating his office. Always an unusually weak governor in his dealings with the legislature, he is on his way to becoming a lame duck. His early vows to address the housing shortage, the homelessness crisis, and California’s high cost of living have come to very little, and he is running out of time to change that.

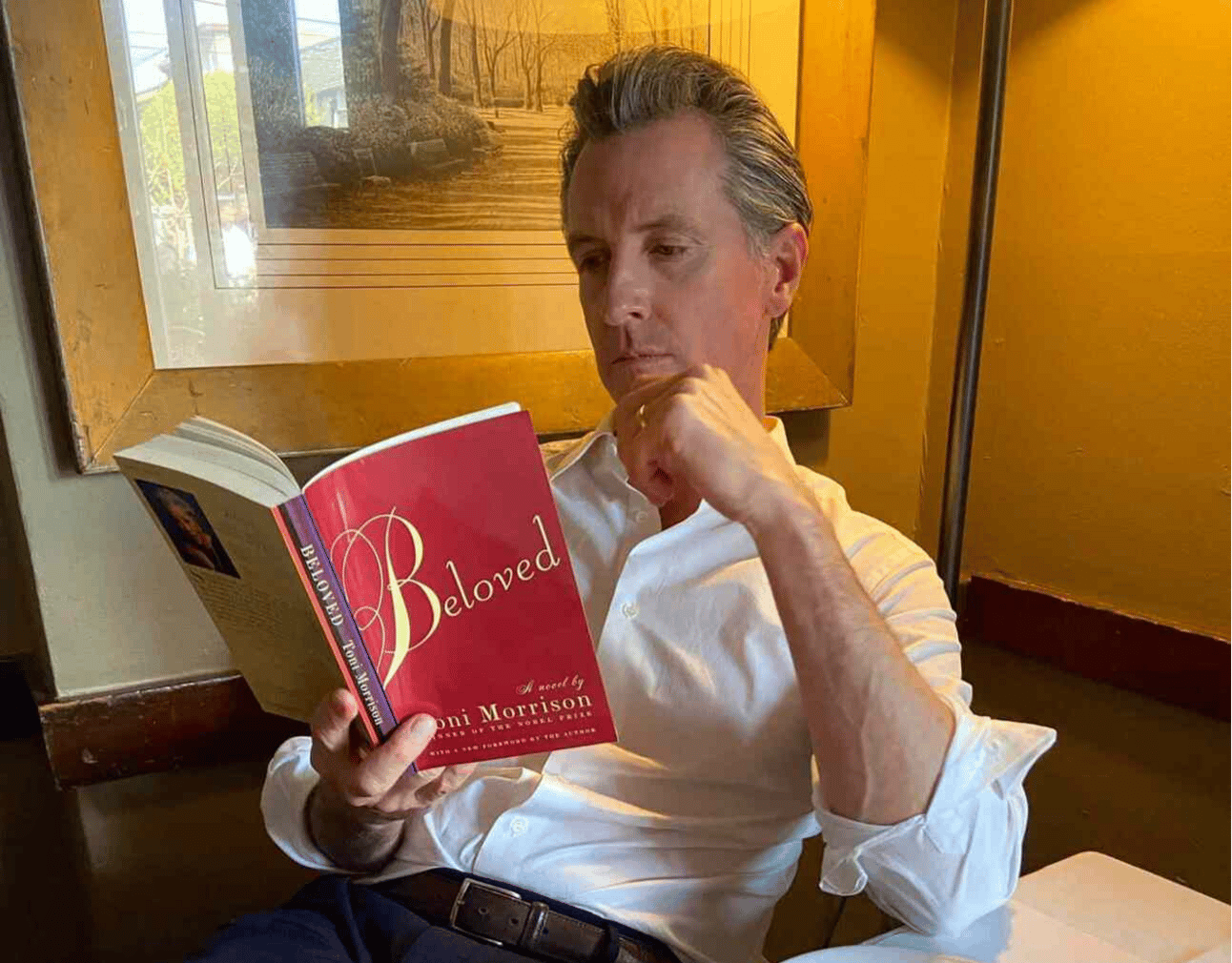

And so the governor has turned to podcasting.

Chris Hayes once dinged Sen. Ted Cruz for turning “his powerful elected position into essentially a part-time job” and dedicating most of his energy to hosting a podcast. Newsom is doing Cruz one better: California’s governor is now the host of two podcasts, one of which he co-hosts with Marshawn Lynch, and Doug Hendrickson.

But it is the second of Newsom’s podcasts — the one where he serves as solo host — that has been getting more of the attention lately. This is the one where Newsom has interviewed a succession of far-right creepazoids, including unreconstructed segregationist Charlie Kirk and confessed fraudster Steve Bannon.

The solo podcast has certainly reintroduced Newsom to a national audience, but not to his benefit. Instead, listeners outside of California can now get a taste of his singularly erratic, insubstantial approach to politics. I’ve heard a lot of speculation about why Newsom would want to enter into dialogue with people like Kirk and Bannon — either he is trying to break with Democratic orthodoxy in order to distinguish himself in the party’s crowded 2028 presidential field, or he is trying to prove that he can hold his own against certified MAGA goons, or some combination of the two — but I think the truth is both simpler and dumber than any grand strategy narrative. Newsom doesn’t strategize; he reacts.

Take the infamous moment from Newsom’s conversation with Charlie Kirk where the governor said he agreed with his guest that allowing trans athletes to play women’s sports is “deeply unfair.” It was a grotesque scene: California is a historic safe harbor for queer people, and here was the state’s governor publicly throwing trans people under the bus while chatting up a professional bigot. But let’s set aside the morality of Newsom’s gambit and evaluate his behavior on its own terms: what was he trying to accomplish, and did he accomplish it?

I’ll start with what he was trying to accomplish. Since the 2024 election, there has been a lot of agonizing in Democratic circles over whether the party should, to put it euphemistically, “moderate on trans issues.” Some of this is in response to the widespread perception that Trump’s campaign did serious damage to Kamala Harris with the ad saying she was “for they/them” instead of you, the voter. Newsom’s seemingly off-the-cuff intervention in his conversation with Charlie Kirk was to reassure him that, actually, Newsom’s own support for they/them is qualified at best. Presumably, Newsom was trying to inoculate himself against some of the attacks that apparently worked on Harris — and to demonstrate his viability as a 2028 presidential candidate in the process.

As for whether Newsom achieved his goal: in the couple months since Newsom’s Charlie Kirk interview, we’ve gotten some polling that sheds light on that question. It doesn’t look great for him.

The good news for Newsom is that most Californians agree with him. According to a poll released last month by the Public Policy Institute of California, almost two thirds of the state’s likely voters “support requiring transgender athletes to compete on teams that match the sex they were assigned at birth, not the gender they identify with,” including about half of Democrats. A more recent poll, published at the beginning of this month, reports that more than 40 percent of the state’s voters think Newsom’s remarks about trans sports are either “a betrayal of his values and the base that elected him” or — the more popular option — “a fake attempt to make people think he is changing.” And along those same lines, a poll from last week shows that a majority of California voters think the governor “is devoting more attention to things that could benefit himself as a future national contender compared to 26% who said he’s paying more attention to solving California’s problems.”

So to recap: Newsom took a position that most voters support, albeit one that divides his party almost exactly in half. A sizable portion of the California electorate, likely including a fair number of people who actually agree with him on the merits, believe his position is fundamentally insincere. And the whole saga has only reinforced his larger weakness in his home state: the (entirely accurate) perception that he spends more time running for president and preening for the cameras than he does governing California.

To my mind, this is a useful parable about the trouble with popularism. The popularist view — most prominently argued by Matt Yglesias and pollster David Shor — is simply that Democrats should embrace positions that most voters support and attempt to raise the salience of them, while either downplaying areas of disagreement with the median voter or modifying the Democratic platform so that it more closely aligns with what most people want. Yglesias has described it as an “an almost childishly silly thing to argue about.” And yes, all else being equal, it is axiomatically true that espousing popular positions is a better political strategy than espousing unpopular ones.

But a politician is not an aggregation of policy positions. Charisma, or lack thereof, matters a great deal. When I talk about charisma in the political context, I’m referring to something more than charm or good looks: following Weber, we might describe charisma as "a certain quality of individual personality by which [the charismatic individual] is considered extraordinary and treated as endowed with supernatural, superhuman, or at least specifically exceptional powers or qualities." This is not something that anyone can manufacture by chasing popular sentiment; as Weber puts it, “charismatic authority is specifically irrational in the sense of being foreign to all rules.” Trump, though he violates every precept of how to behave like an American politician or statesman, is intensely charismatic; so is Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez, even though avowed socialism isn’t especially popular with the median voter.

Charisma implies a certain solidity or substance: charismatic people insist on themselves through their very presence, seemingly without even trying. And by that standard, Newsom, despite his good looks — he may never be president but he could definitely play the president in a mid-tier Netflix movie — is deeply uncharismatic. There is nothing there to grab hold of. Instead, Newsom exudes nothing more or less than a transparent hunger for recognition and the next rung of the cursus honorum. Where there should be substance, there is vacuous need. And in that context, every pivot to the next thing, to the more popular and attention-grabbing stance, is actually a liability because it draws further attention to the basic hollowness of Newsom’s political persona.

I’ve always been skeptical that Newsom has a serious shot at becoming president. The way things are going right now, I’d frankly be surprised if he won the 2028 primary in his own state. But if his podcast were solely an exercise in self-harm, it would be difficult to care too much. Instead, all this frantic activity is corrupting the state’s governance. (Recall that governing the state is still technically his full-time job.)

Newsom’s comments in the Charlie Kirk episode did not just affect his own political standing. When the governor of your state weighs in on a hot-button topic, it moves things in state politics. Single-handedly, Newsom briefly placed trans athletes near the top of the state legislature’s 2025 agenda: suddenly Republican legislators, who had introduced two clearly DOA anti-trans bills at the beginning of the year, could claim they were aligned with the governor’s office on this one issue. Media attention gravitated toward the two Republican bills, eating up finite attention that could have gone to, for example, legislation addressing the state’s housing shortage. And of course, this also meant that LGBTQ allies in the legislature’s Democratic caucus had to take a stand on the bill. Newsom, by trying to align himself with a popular stance, maneuvered his own party’s legislative caucus into a position where they had no choice but to publicly oppose — and, in fact, vote against — this stance.

Newsom wasted the legislature’s time, antagonized legislative leadership, and forced Democratic legislators into an awkward position in exchange for basically nothing. In an interview with the Los Angeles Times, he had to lamely clarify that there was no “grand design” behind his remarks — he had given no consideration to how they would affect the actual business of running California, because the business of running California apparently doesn’t interest him.

I haven’t focused so much on the Charlie Kirk interview because I think it’s a particularly significant moment in Newsom’s tenure. Instead, I’ve chose to examine it at length for two reasons: first, because it drew so much national attention, and second, because I think it reveals a lot about Newsom’s relationship to governance and political communication. It nicely sums up the pattern of his two terms as governor. As the second term sputters out, we can start to consider his administration as a whole; what we see looks a lot like a long parade of missed opportunities.

Things could have been very different. Imagine a governor who instead chose some big priorities early on — actually getting all that housing built would have been a good one — and stuck to them. This governor would have worked to establish strong relationships in the legislature and provided clear, consistent directives to his own cabinet-level agencies. Our hypothetical governor would then have an actual record of achievements he could point to when running for president.

This governor need not be a “deliverist.” Good governance alone is not necessarily sufficient for winning national elections. (Although bad governance doesn’t help, particularly when it chafes other political heavies in one’s own state.) Symbolism and communication obviously matter a lot. But how and to what extent they matter depends a great deal on the charisma of the communicator.

Charisma may sound like a frivolous concern, but it actually becomes more important in moments of crisis. Particularly when the foundations of the republic are cracking, and when it feels like a dark chasm is opening up directly beneath our feet, we need politicians who can speak and act with gravity and authority. We need people who can convincingly articulate a way out of the Trump era, and who exude the sort of command that makes voters believe they can lead the way. The sort of public flailing we’ve seen since the election from a number of Democrats — Newsom among them — is worse than undignified, because it isn’t just the personal dignity of the flailers that is at stake. This country and this state both deserve better.